.

ART+AUSTRALIA VOL 48.1 SPRING 2010

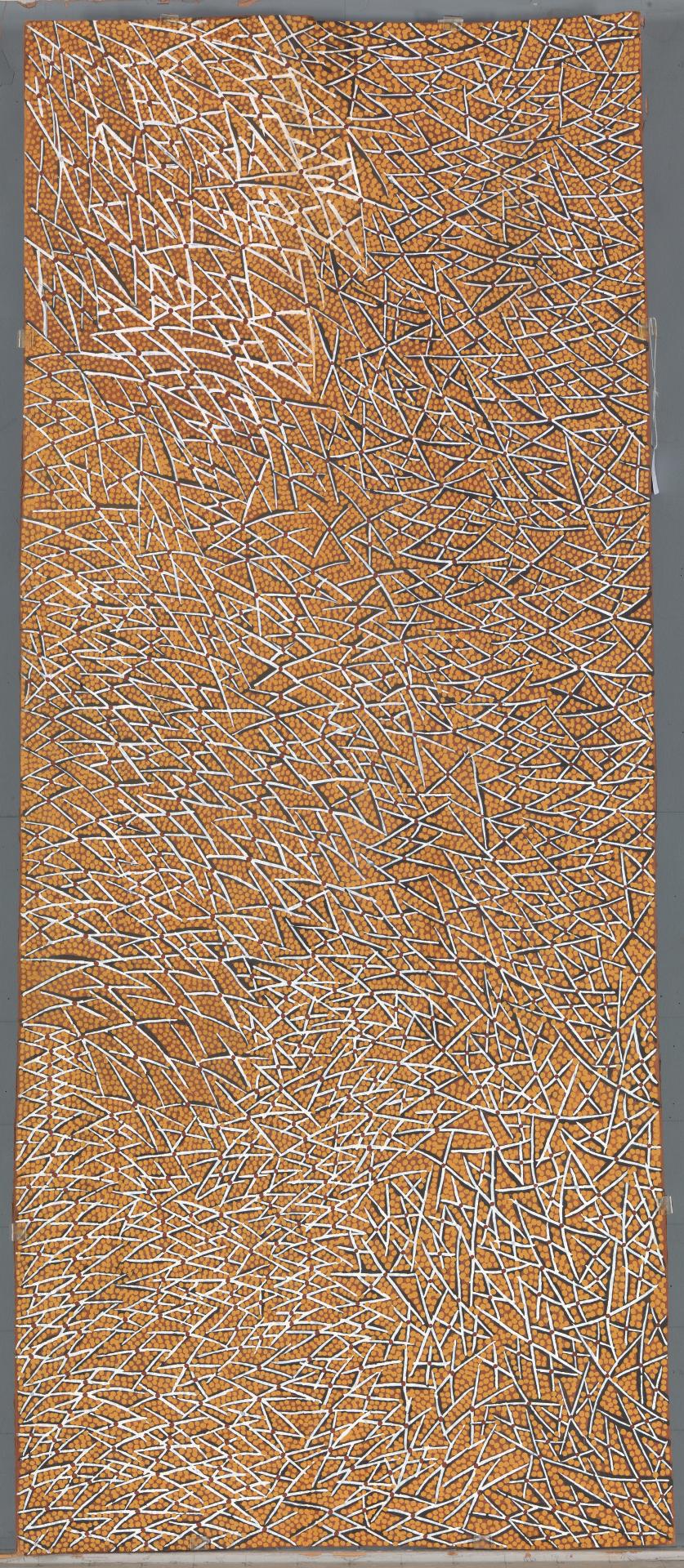

GULUMBU YUNUPINGU: INTO THE LIGHT

ELINA SPILIA

THINGS ARE NOT ALWAYS AS THEY SEEM. If we ease the hold of our eyes and open our senses to  darkness, if we loosen our flesh to expose the bones beneath, we may glimpse it. Attentive to the transformative qualities of shadow and illumination, the Yolngu people are mindful that the darkness is also a kind of light periodically revealing the stellar landscape hidden behind the diurnal sky. The transitions between visibility and invisibility offer revelatory thresholds where the surface may betray the substance it conceals. Form is a ruse, for anything of consequence is never simply contained.

darkness, if we loosen our flesh to expose the bones beneath, we may glimpse it. Attentive to the transformative qualities of shadow and illumination, the Yolngu people are mindful that the darkness is also a kind of light periodically revealing the stellar landscape hidden behind the diurnal sky. The transitions between visibility and invisibility offer revelatory thresholds where the surface may betray the substance it conceals. Form is a ruse, for anything of consequence is never simply contained.

It is little wonder, then, that the trajectory of Gulumbu Yunupingu’s work displays an incremental departure from form, a gradual dematerialisation that accompanies a deepening conceptual practice. Yunupingu’s signature starscapes on sheets of bark and hollow eucalypt trunks have more in common with the performative than the painterly. She titles them simply Ganyu (stars) or Garak (Universe), and they form a single body of work that has sustained the core of her artistic practice over a period of ten years.

Yunupingu’s career as a commercial artist began in earnest in the late 1990s, and her first star shapes—unconsciously resurrected from paintings made by her father, the acclaimed postwar painter Munggurrawuy Yunupingu—featured on small barks illustrating Yolngu ancestors associated with astronomical phenomena. Most significant to Yunupingu’s later work is the narrative related to the constellation of Djulpan. In a Promethean drama played out each night a constellation of ancestral women paddle a canoe towards the western horizon through vast celestial waters, fleeing a constellation of men paddling after them through the aqueous night. In its sacred permutations, this narrative and the sacra derived from it is one of the means by which Yunupingu’s Gumarj lineage (together with other Yolngu groups) is linked to an ancestral realm that joins terrestrial and celestial geographies. The heavens are animate with traces of ancestral activity evident in the changing landscape of the night sky.

From these illustrative beginnings, Yunupingu isolated the star motif and painted starscapes divided into panels of different colours. Soon after, the divisions in her work disappeared, leaving shifting fields of hue and form, reducing the star motif to a mere gesture. Cross-like linear markings interspersed with dots impart a fluidity and movement enhanced by the uneven surfaces of bark. At their most impressive these bark paintings appear to hang like rippling sheets or veils, their pigments glowing with a silken sheen.

Yunupingu was among the first painters in the Yirrkala region to depart so decisively from the characteristic paint styles of north-east Arnhem Lane, which are typically either illustrative in their emphasis or bear sacred ancestral designs. The calibre of her work was quickly evident. Yunupingu’s distinctive style inspired a new genre of painting in the region, evident, for example, in Boliny Wanambi’s and Ralwurrangji’ Wanambi’s paintings of swarming bees and mosquitos. In 2004 Yunupingu won the National Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Art Award with three star poles titled Garak-the Universe. Following the 2006 unveiling of her designs at the Museé du quai Branly in Paris, she was recently commissioned to incorporate her starscapes into the centrepiece of the Australia National University’s new building for studies in Asia-Pacific diplomacy and allied studies. Her life-sie Macassan prau sailhonours several hundred years of Asian-Australian exchange, which was particularly scute in the economic and cultural relations between Yolngu and Macassans. At the recent 17th Biennale of Sydney her work formed part of an installation Larrakitj, an unsurpassed collection of painted memorial poles from north east Arnhem Land which were acquired over more than a decade by Anne Brody for the Kerry Stokes Collection. Until late October this year Yunupingu’s work is being exhibited in the Australian Pavilion at Shanghai World Expo 2010 ahead of private shows in China and Singapore. But while her work is highly regarded, it is not well understood.

The artist describes her star motif as a figure comprising a body, a spirit and an eye from which it may ‘cry’, a double reference to the idioms of night rain falling from the ‘eyes’ of crying stars and the keening liturgies performed by senior Yolngu women. The latter are weeping songs of compassion and lament which provide restoration and comfort and celebrate a natural order preordained by ancestral action. Yunupingu regards her painting as possessing a similar restorative quality, part of a broader life’s work as a practitioner of Yolngu medicine and an astute mediator, diplomat and political leader.

Yunupingu’s oeuvre has largely been framed in terms of a painterly practice that conveys a universalist or humanist metaphor—a world encircled and unified beneath a single night sky or an earth reflected in a heavenly mirror. At a deeper level, she is concerned with the nature and limits of knowledge, the utter incomprehensibility of the universe, the tantalising threshold that tethers us to our humanity and holds us back from the mysteries of the scientific and divine. This limit is reached in the beauty, awe and human fragility inspired by our fleeting nightly interface with the fraction of the universe perceptible to human sight.

A growing sensitivity to the conceptual aspects of Yunupingu’s work has eld to its increasing exhibition as a synthesised installation rather than as a display of discrete objects. Since 2009 Yunupingu’s Melbourne gallerist, Beverly Knight, has exhibited her work as an immersive environment, situating viewers within a celestial landscape. As we walk through a woodland of star poles, we find ourselves in the blackness between galaxies—or, more precisely, in the interstices the artist has created between fragments of space. Yunupingu casts the viewer into the metaphoric space of her conceptual concerns—the limits of human perception, investigated through the spatial metaphors of the edges of the universe and the territory between life and death. ‘We don’t know what is after the last stars’, the artist has told me, ‘we don’t know what is beyond’. Through the simplicity of the star motif, her work elegantly transposes questions that have vexed the most accomplished scientific, humanist and theological minds into a seemingly effortless distillation of Yolngu aesthetics and philosophy. Though these are secular artworks, from her immersion in sacred art traditions Yunupingu uses the act of painting as a conduit—an activity that becomes a revelatory process and an internal meditation performed across hundreds of objects. She rests the nature and limits of knowledge, painting the night sky star by star, as if by painting each one she might discover the finitude of the universe and reach beyond its edge. Each painting is a fragment of a whole, part of a performative documentation of the apparently expanding universe.

In the cavity of her star poles, Yunupingu offers us a second spatial metaphor that linsk the objects, the night sky and Yolngu metaphysics concerned with the transition between life and death. Yolngu regard the cavity of the memorial pole to be a space of metamorphosis and a channel to the ancestral realm. Prior to the prohibition of customary Yolngu funerary practices, hollowed eucalypt trunks were used as repositories for the final interment of human remains purified of mortal flesh and reduced to a symbolic spiritual core:bone. They were consecrated by the application of sacred designs to assist the Yolngu spirit to return to its place of ancestral origin by uniting the ochred bones of the deceased (the residue of the spirit), the bones, of country (sacred places), and the bones of ancestors (sacred objects and their designs). In certain Yolngu funerals, the sanctified memorial pole (or its contemporary counterpart the coffin) becomes the symbolic vehicle for the final journey of the spirit through an ancestral geography, a vessel which carries the spirit of the deceased through metaphysical landscapes (aqueous, celestial, terrestrial) which Yolngu regard as immanent and fleetingly perceptible beneath the surface of the world we inhabit.

The principle that meaning exists beyond visible perception is a central tenet of Yolngu philosophy that finds specific application in Yolngu aesthetics. Yunupingu wraps surface around substance, painting her starscapes around a cavity in which matter, space and time are thought to be reshaped in mysterious ways. She paints the hollow by painting the surface by probing the depths of the darkness by painting the light. With a mind-bending logic typical of Yolngu epistemology, the visible surface of the object is both a revelatory mirror and a translucent veil to the substance hidden inside. According to Yolngu scholarship, an invisible or semi-visible trace may indicate an intrinsic but obscured presence or power that holds profound and hidden meaning. Astrophysicists provide us with an apt analogy: each star is a perpetually changing state of energy and matter momentarily perceptible within the scope of human senses. Astronomical bodies are not perceptible on themselves, they are visible only through fragments of light beamed across unfathomable light years; eye and light join across distance and time to provide traces of an ancient past manifest in the present.

Memorial poles were historically erected in an ancestral estate of the deceased and left undisturbed to be reabsorbed by the land. This dematerialisation paralleled the separation of the spirit and its journey back into the spiritual homeland. For some Yolngu, this spiritual homeland is the night sky, hence some stars are considered to be the spirits of unborn children waiting to be born. In a curious parallel of cultural relativity, astrophysics tells us that all human life is created from the debris of stars. As a star approaches death, its heart cools and slows until the celestial body collapses, exhaling to a fraction of its size before bathing the darkness in searing light. In the vacuum of space, the supernova explodes in majestic silence, hurling billion-year-old debris—carbon, oxygen and nitrogen—into the blackness. The scattered ashes of dead stars form the elements of human life.

Equally compelling is the fact that despite the array of their forms, mass and energy are finite; recycled, for example, between sound and motion, heat and light, energy and matter. Yolngu regard the body’s dematerialisation and the spirit’s transformation within an analogous framework, made possible by the transformation of ancestral substances and forces. As it happens, Yolngu cast aesthetic affect into a continuum of song (sound), dance (motion), optical effects described as shiny or brilliant (hence connected with light), and the power of objects, places and painted forms (matter). Things are not always as they appear. A visual form may therefore be described as an apparition of ancestral sound or motion, an alternative manifestation of an ancestral force. Consequently, Yolngu art has always been (albeit in a very specific sense) post-medium. In painting the surface Yunupingu paints the space it conceals, the threshold between the known and the unknown, the boundaries of human knowledge. Form is a ruse, because anything of any consequence is always, also, something else.

Gulumbu Yunupingu 'Ganyu', 2009

earth pigments on Stringybark (Eucalyptus sp.)

National Gallery of Victoria, Melbourne

Gift of Margaret Bullen through the Australian Government's Cultural Gifts Program, 2014

© The Estate of Gulumbu Yunupingu, courtesy of Buku-Larrnggay Mulka Centre, Yirrkala