Art + Australia | Outside

Art + Australia. 2019. Issue Six (56.1): Outside

NOW AVAILABLE

Outsider Art in Australia: Artists’ Voices Versus Art-world Mythologies

Anthony WHITE, Anna PARLANE, Grace MCQUILTEN and Charles Green

Q: Have you ever come across the category ‘outsider art’? … What do you think of that phrase in terms of a way of describing artwork?

A: Automatically it has a negative look … because you think if they’re not qualified, they’re not a true artist. But I don’t believe I’m not qualified … It’s an interesting word because it doesn’t necessarily lack authoritativeness in the word but the meaning of it does … I think it’s good to use it but it maybe needs a bit of an explanation to it.

Mark Smith, interview with Anthony White and Anna Parlane, 2019 [1]

With the rise of outsider art institutions, exhibitions and markets internationally in recent decades, it has become apparent that the romanticisation of artistic difference that is endemic to discussions of the field is misplaced. While so-called ‘outsider artists’ are conventionally typecast as pristine cultural isolates, in fact they are not only deeply engaged with the social, political and artistic worlds around them, but are often also aware of the terms being used to describe their work.

The highly contested term ‘outsider art’ has historically been adopted by scholars, curators and critics—as well as some artists—to encompass the work of people with disability, those with experience of mental illness or incarceration, non-tutored or naive artists, and visionary artists. While such art was commonly viewed during the 19th century as evidence of ‘degeneration’, in the 20th century it received a more positive interpretation by the likes of Jean Dubuffet and Roger Cardinal for being free of conscious artifice, bypassing culture, and producing a documentation of inner life. Regardless of whether outsider artworks were denigrated or romanticised, their categorical segregation from mainstream art resulted in misunderstanding and misrepresentation. Recent studies of the work of the Mexican-born American artist Martín Ramírez, for example, have challenged the presumption of early commentators that his work was primarily a manifestation of his schizophrenia, pointing out the references to vernacular Mexican architecture and folk Catholic imagery that ‘should have been obvious from the start’. [2] Furthermore, as is evident in Mark Smith’s comments above, artists who have been categorised as ‘outsiders’ often have a critical perspective on the idea and category of outsider art and are aware of both its limitations and potential usefulness. A major gap in the discourse around outsider art has been, and continues to be, the voices and agency of artists who have been given this categorical definition. How might the views of artists inform, and potentially transform, a contemporary understanding of outsider art?

[1] Mark Smith, interview with Anthony White and Anna Parlane, Arts Project Australia, Melbourne, 22 May 2019.

[2] Daniel Wojcik, Outsider Art: Visionary Worlds and Trauma, University Press of Mississippi, Jackson, 2016, p. 23. See also Víctor M. Espinosa, Martín Ramírez: Framing His Life and Art, University of Texas Press, Austin, 2015.

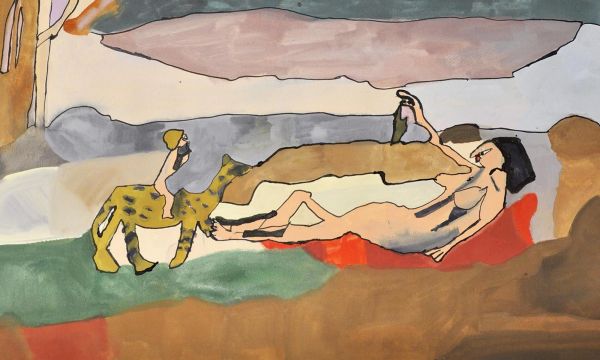

Image: Paul Hodges, Girl and a Tiger, 2015, Gouache and ink on paper, 38.5 x 76.5 cm